ACW JOURNAL

Artists Interviews

Exhibition Reviews

ACW Contributing Writers

CLAUDIA CHENG CURATES AN EXHIBITION OF WOMEN ARTISTS EXPLORING SPIRITUALITY FOR ARTSY

Words by Olivia Wilson

‘Window to Her Soul’, featuring both emerging and established female painters, places the exploration of spiritual themes at its core. When curating the show, the link between art and spirituality is what drove Claudia Cheng, the curator. “With this show, I wanted to impart the idea that art can be a vessel to connect humans with spiritual awareness”, Cheng shares. Indeed, since the early 20th century, female artists such as Hilma Af Klint, Hilla Rebay, Georgiana Houghton and Emma Kunz have employed art as a language to explore spirituality. The works in this exhibition serve as visible proof of the spiritual, intangible world beyond the practical one. Regarding this, Cheng says she “hopes these works may enlighten the viewer and give rise to the spiritual awareness that all living forms are connected in harmony with the universe”.

By focusing on the spiritual, ‘un-seen’ aspects of femininity and the female experience, Cheng erodes the archetypal view of women throughout art history as objects of male, sensual desire. Portraying the female psyche from a woman’s perspective shifts the archetype of femininity and sheds critical light on other aspects of the female experience such as the emotional journeys of growing into our bodies or giving birth to life.

Molly Greene, Insinuator, 2021. Source: Artsy

The selected artists are united in their rendering of inner spiritual experiences, rather than external realities, and their adoption of art as a language through which to grapple with spirituality. These artists are visionary peers of the likes of Hilma Af Klint (1862-1944, Sweden), whose mystical works paved the way for the development of Surrealism and Abstract Art. Collectively, ‘Window to Her Soul’ is a manifestation of the subconscious: the paintings give expression to the invisible by portraying the liminal space between the physical world and the mind, which Af Klint sought to portray decades prior.

Hilma Af Klint, Group IV, no 5, The Ten Largest, 2018. Source: Artsy

Anna Zemankova’s abstracted, womb-like flora embody the female experience. Rendering her inner thoughts onto the canvas, Zemankova confesses: “I grow flowers that grow nowhere else”, referring to her inner world and subconscious. Comparatively, Loie Hollowell’s colour-saturated, geometric compositions emerge from recurring lamentations regarding sex, pregnancy and the embodied female experience. Like Zemankova’s imagery, Hollowell’s organic forms allude to the female anatomy or planetary shapes, lending a cosmic resonance to intimate, feminine, experiences.

Loie Hollowell, Split Orbs in Grey, Yellow and Purple, 2021. Source: Artsy

Megan Rooney’s multi-disciplinary practice similarly remains centred on the politics of the female body. ‘Stand Up Sky’ is an expressive work with thick swathes of paint, amidst which finer lines echo the outlines of figures half emerged. Rooney’s painting presents layers of ethereal forms, sanded back and then painted over once again multiple times. Ultimately, through this process, abstracted narratives emerge that lack a discernible beginning or end.

In her practice, Vika Prokopaviciute adopts purely abstract vocabulary. Using perfectly complimentary tones, Prokopaviciute blends poetical influences with a methodological approach.

Vika Prokopaviciute, Sticky Quattro Side View, 2020. Source: Artsy

Elena Alonso masterfully orchestrates a palpable, unsettling tension between the neat, uniform beauty of her compositions and the uncertainty of what it is exactly one sees. By utilising the language of architecture and design, Alonso in turn “liberates [the paintings] from their inherent practical purpose” (Fabian Lang Gallery, https://www.artspace.com/artist/elena-alonso). The calculated architecture of Alonso’s formal compositions is comparable to that of Af Klint, which are almost entirely devoid of representational content, equally comparable to the work of Prokopaviciute.

Laura Berger’s practice is stimulated by a myriad of influences: dreams, nature, travel, our unending quest for self-development and, how we attempt to construct a sense of belonging to the greater whole. Berger states, “I like to use painting as a way to explore questions that no concrete answers – ideas which exist on a more spiritual and emotional plane”. Berger continues, “the figures in my work are meant to represent everyone, with external identifiers of race and age removed.” With these ‘external identifiers’ absent, Berger heightens the elasticity of the female spirit.

Berger, along with Robin F. Williams, are the only two figurative artists included in ‘Window to Her Soul’. Williams’s ‘Shadow Family’, much like the work of Alonso, is unsettling. Simultaneously otherworldly yet mundane, ‘Shadow Family’ depicts a couple and their child sat in between them. Reflecting something uncomfortable, yet simultaneously unidentifiable, about society and culture, ‘Shadow Family’ is rendered in the artist’s characteristically vibrant colour palette.

Robin F. Williams, Shadow Family, 2021. Source: Artsy

London-based curator and art advisor Claudia Cheng considers it both essential and invigorating to support the work of young, contemporary female artists, who are at the forefront of shaping the future of the art world. Despite the recent progress towards increasing female representation in art institutions, much work still needs to be done to continually support and celebrate the work of female artists and achieve gender parity.

Photo of Claudia Cheng

Cheng recognises the benefits of collaboration and harnesses technology as a tool to connect, converse, and, ultimately, lift others up. Cheng’s ethos signals a new direction in which the art world is headed: a new landscape of females working collaboratively is opening up. Ultimately, Cheng’s curatorial process “is both an investigation of art history and an open dialogue with contemporary artists”. ‘Window to Her Soul’ is testament to this, uniting female artists whose practice is deeply connected and of similar inspiration: what is means to be a woman.

Words by Olivia Wilson

THE REALITY IN WHYTCH YOU CREATE

Words by Alison Lo

What constitutes a London dream in the post-Brexit era? At a discreet street corner in bustling Notting Hill, a star shines bright in the dark – Studio West, a new gallery pioneered by curator Caroline Boseley. For their inaugural group show, The Reality in Whytch You Create, Caroline showcases a selection of works by five emerging London-based artists; Sholto Blissett, Lydia Makin, Alfie Rouy, Anna Woodward and Salome Wu. The exhibition explores reality in an expanded sense and invites the viewer to experience the boundary between dreams and reality.

“The world of reality has its limits; the world of imagination is boundless.” –

Jean Jacques Rousseau

Molly Greene, Insinuator, 2021. Source: Artsy

The title of the exhibition derives from one of the dream-like works created by artist, Alfie Rouy, titled “The Reality in Whych you Create is Swyphtly Healed by Devotion to Good!”. Rouy adopts a surrealist approach to his work and presents an eerie, other-worldly universe, with a recurrent stream of light gleaming from his paintings. In a parallel universe, Anna Woodward renders a utopian illusory view of a botanical garden filled with blooming vibrant plants and arboreal insects – an underground party devoid of human presence.

Alfie Rouy, The Realty in Whych you Create is Swyphtly Healed by Devotion to Good!, 2021, Acrylic on Canvas. Photo courtesy of Studio West Gallery.

Time and fragility are central to Salome Wu’s multi-media practice. In her video installation piece; 'The Wind Stood Still, Dancing Silently', the emergence of a female figure above the water invokes a sense of liberation beyond the confines of reality. On the other hand, Sholto Blissett unveils a surreal imaginary landscape free from human beings, transporting the audience into a space of serene tranquility, with the interplay of light and architecture. In his diptych, Garden Study, the cloudy sky reflects on the pine trees against a backdrop of distant mountains while a calming waterscape is depicted in the foreground.

Sholto Blissett, Garden Study, 2021, Oil on Board (Diptych). Photo courtesy of Studo West Gallery.

Wandering through the exhibition space, one questions what is real and what is imaginary. The surreal depictions of space combined with the unearthly characters, transport the viewer into a new kind of reality, one that invites personal imagined perceptions. A question springs to my mind: Can dreams ever become real?

In line with Studio West's vision, the group show elevates the work of emerging artists and aims to create an authentic dialogue with the local community of Notting Hill. Alongside the exhibition, the gallery is hosting a number of events, including a meet-the-artists session on the evening of February 4th, moderated by Hector Campbell.

Words by Alison Lo

'The Reality in Whytch You Create' is currently on view at Studio West Gallery until 17 February 2022.

For more information visit here.

Gala Bell – Breaking the Boundaries of Art

Words by Olivia Wilson

A deep fried oil on canvas, a classical bust constructed out of sugar and steel, an installation made from noodles submerged in a tank: the delightfully varied artwork of Gala Bell defies classification, pushing the limits of what art is. The alchemy of matter lies at the centre of Bell’s practice as she explores material combinations and methods that expand the methods of art making. Studio come kitchen/ lab, Gala creates new processes, meanings and possibilities.

Gala Bell, Pomegranates, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

The most intriguing artistic process of Bell’s is her deep-fried paintings. Deep-frying is in fact a ritualistic purging, originating from missionaries in Portugal who used it as a way to fulfill fasting and abstinence rules around the ember days, Quattuor Tempora. It travelled to the port of Nagasaki and detonated as a popular street food. Hot oil, refried again and again, glows like gold on the surface of Gala’s works and is just one of the ways she enacts material transformation. The process of deep-frying also, surprisingly, shares ingredients with painting: egg yolk tempura, linseed oil mixed with pigments. Through this process Gala also passes commentary on the defined distinctions of taste: ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture as well as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste. One might consider an oil painting far too important to deface with being deep-fried. Social inequalities are reinforced and perpetuated on the basis of cultural distinction, whilst invisible market forces lead us to a cultural condescending of some tastes above others. Therefore, by deep-frying a cultural object, such as an oil painting, Gala revels in the cross over between stereotypical ‘high’ and ‘low’ tastes.

Gala Bell, Fry Up, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

In Supernatural Infatuation, Bell submerges oversized noodles in a tank, lit from within by LED lights. Yet again the distinctions of studio/ kitchen/ lad are evaded in favor of scientific artistry. Installation or chemical experiment, it might be difficult to tell if one were to encounter this work. However, Gala sees these more experimental works as just one part of her practice. Gala is also a teacher, creates more ‘commodified’ works such as paintings and creates silk items one can purchase. Clearly, Gala delights in the thrill and challenge of specialising in numerous different mediums and materials.

Gala Bell, Supernatural Infatuation, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Indeed, materials: their textures, appearance, colours and how they compliment or contrast against each other, is a great inspiration to Gala. If ever in a rut Gala takes inspiration from watching someone else make something. However, escaping a rut is easy Gala confesses, as she has utilised so many different techniques and methods of making throughout her artistic career.

Courtesy of the artist.

Despite her mastery over many different materials and artistic skills, painting is Gala’s current favourite medium to work with. However, simultaneously, Gala favors other viscous, less conventional, materials such as motor oil, silicone, hair gels, sugars and syrups: anything that can be poured and will reflect and interact with light in a specific way. Gala says: “So much of my early painting work looked at creating that effect of light, it eventually came through in the sculptural work also. I love the way that artists like Dahn Vo, Rebecca Warren, Michael Dean, Samara Scott create from the mess of experience. The play and interaction between materials is really exciting and it offers a different way of thinking and feeling an artwork that pure painting cannot. But there is also a sentiment that painting offers that is unmatchable compared to a readymade, so it really depends on which way the pendulum swings.”

Gala Bell, Equilibrium, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Varied and experimental: nothing is out of bounds for Gala. Gala describes her practice as “transitional: a passage or changeover to something else”. Moving back and forth, ideas constantly morph and evolve, clashing or contradicting; Gala revels in the unpredictability: not knowing what might take shape.

About Gala

A graduate of the Royal College of Art and Guilds City Art School, Bell was recently announced as one of Ashurst’s Art Prize 2021 shortlisted artists. Bell has also been selected for inclusion in exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the London Design Festival; The Design Museum, London; and the Kunsthalle am Hamburger Platz, Berlin.

Words by Olivia Wilson

Fertile Spoon

Words by Olivia Wilson

A cake stand, displaying curious things: slices of cake (unsurprising), alongside an upturned nose, a sleeping swan and other paraphernalia, whilst a human-like form rests above it, a creature escaping from its mouth like an exorcism. In another painting, two globular beings hold seemingly intense eye contact, a spoon extending from the mouth of the larger, salmon pink being, a pure white light shining in the background. Sounding like the descriptions of strange fever-dreams, the content of both Stephenson and Pailthorpe’s fantastical paintings is playful, bizarre and disordered.

Grace Pailthorpe, June 3rd 1938 (1938). Courtesy of Bosse & Baum.

Born over a century apart, both Mary Stephenson and Grace Pailthorpe bring to life the mysterious, sometimes unarticulable, logic of dreams. Pailthorpe was a controversial figure in the Surrealist movement, having been expelled from the group in 1940 due to her refusal to heed the group’s cohesive doctrines. Trained originally in psychoanalysis and psychiatry, Pailthorpe latterly turned to painting and committed to portraying what loiters in the depths of our subconscious. Typically depicting organic matter: bodily fluids, umbilical cords, fetal forms, Pailthorpe’s works typically focus on biology and juvenile psychological processes. Stephenson, a contemporary artist currently studying at the Royal Academy Schools, also adopts a Surrealist language in her work. When regarding Stephenson’s works, one encounters a sad cucumber, wine bottles as shoes, a face melted into a napkin. Undoubtedly, in both artists’ work, the dream world is abundant with intrigue.

Grace Pailthorpe, 27th July 1948 (1948). Courtesy of Bosse & Baum.

Anxieties awaken in Pailthorpe’s works as the curious imagery of the unconscious is articulated on her canvases. The titles of her paintings are mere dates, time stamps, in reference to the night the dream was had. More abstract in form, there is a palpable naiveté present in Pailthorpe’s work. Indeed, “regression to childhood and even, in Pailthorpe’s case, to the womb, is of central concern to both artists”, as Chloe Nahum points out in the accompanying Curator’s text. Living under the firm control of the Plymouth Brethren church’s strict commandments, Pailthorpe’s work is a childish, belated substitute for having lived her formative years in abject terror.

Mary Stephenson, Salt (2012). Courtesy of Bosse & Baum.

Much like psychoanalysts seeking to decode the latent meanings lurking in dreams, one endeavours to make sense of the wondrously bizarre content of Stephenson’s canvases. In Blue Jug, bodies fizz and dissolve like bubbles in a glass of champagne. The scene, appearing to be taking place at the bottom of an endless pool, submerged underwater, lurks in obscurity between a dream and a nightmare. Indeed, Stephenson is concerned with how the unconscious can obscure even the waking world, both obfuscating and revealing physical reality. Stephenson depicts the ways our thoughts morph and meld into comprehension.

Mary Stephenson, Blue Jug (2020). Couresty of Bosse & Baum.

As a whole, the vibrant mustard yellows and fiery reds used by both artists create cohesion. A central, cerulean blue wall in the exhibition space provides a rich contrast to these vivid hues. Indeed, as Chloe Nahum aptly writes, in this exhibition “the unconscious rules the roost, and does as it pleases with paint.” Not only is the content equally weird, but also equally vibrant. Simultaneously disturbing and delightful, ‘Fertile Spoon’ revels in the strange.

‘Fertile Spoon’ is on display in Bosse & Baum’s Peckham gallery until 22nd May 2021.

Words by Olivia Wilson

Get a Load of This!

Words by Isabella Hill

Having opened at Daniel Raphael, London on May 1st and open until the end of the month, Get a Load of This! has been curated by Mollie E Barnes. Known for her work as an independent curator and her Instagram page, @she_curates_ . Mollie has brought together works by 25 international female and non-binary artists to explore imaginings of the female form. Exploring themes of the male gaze, identity and self-reflection, each work is unique in their vision of the female body, yet all complement each other beautifully within the context of the gallery space.

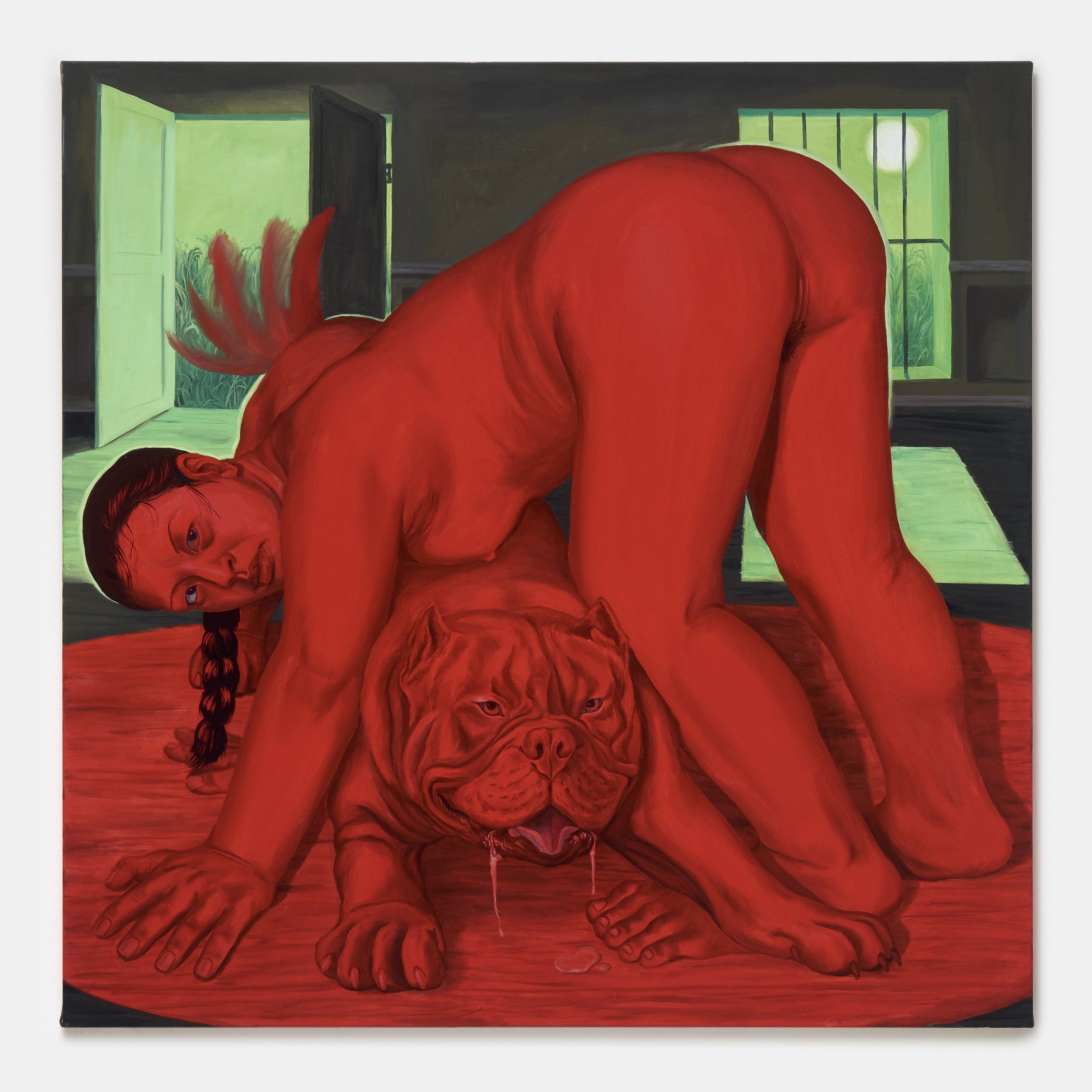

Amanda Ba, Woman Releasing Dog Fart / The Bitch is Non-sense (2021)

Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

What most struck me upon entering the gallery space was how well it suits the exhibition. As a gallery that was originally a house, the mixture of the domestic space with the various depictions of the female form create a sense of intimacy that is not often found in galleries that employ the white cube aesthetic. With natural light pouring into the ground floor room, the images appear brighter and emphasise the ethereal quality of the paintings in this room. Many of these artworks contain an element of surrealism, subverting traditional representations of the female form in a multitude of ways. One artwork that grabbed my attention immediately was Lise Stoufflet’s Pleurer le ciel (2021), depicting a close-up of a woman’s face as she cries tears of the sky. The rich hues of the sky in her eyes in contrast with the subtler pink tones of her skin and hair create a sense of mystery and intrigue as we are unable to identify this crying woman. This work is placed alongside Rebecca Sammon’s work entitled Beach Body Under the Stars (2021), which follows a similar colour palette that presents a female figure bending over and looking directly at the viewer. The vibrancy of the work and the positioning of the figure invites the viewer to stare, as she takes back the sexual agency and power from the viewer through challenging preconceptions of the male gaze. Gone are soft-hued paintings of the female nude, such as in works by Francois Boucher, and are now replaced by bold and opaque colours with women that invite the viewer into the compositional space. Artist Amanda Ba’s work Dog Woman Releasing Dog Fart / The Bitch is Non-sense (2021) portrays a similarly nude figure, bending over. Eroticism is brought to the forefront of the painting in her pose and gaze at the viewer, as the artist subverts the male gaze through such an upfront approach to the sexualisation of the female form. The opposing red and green hues employed by Ba give the effect of a photograph being developed in a dark room, adding to the surrealist nature of the painting. The interplay between the figure and the bulldog serves to remind the viewer that we must revaluate our relationship between species, highlighting the importance of cohabitation and valuing other species just as much as we value ourselves.

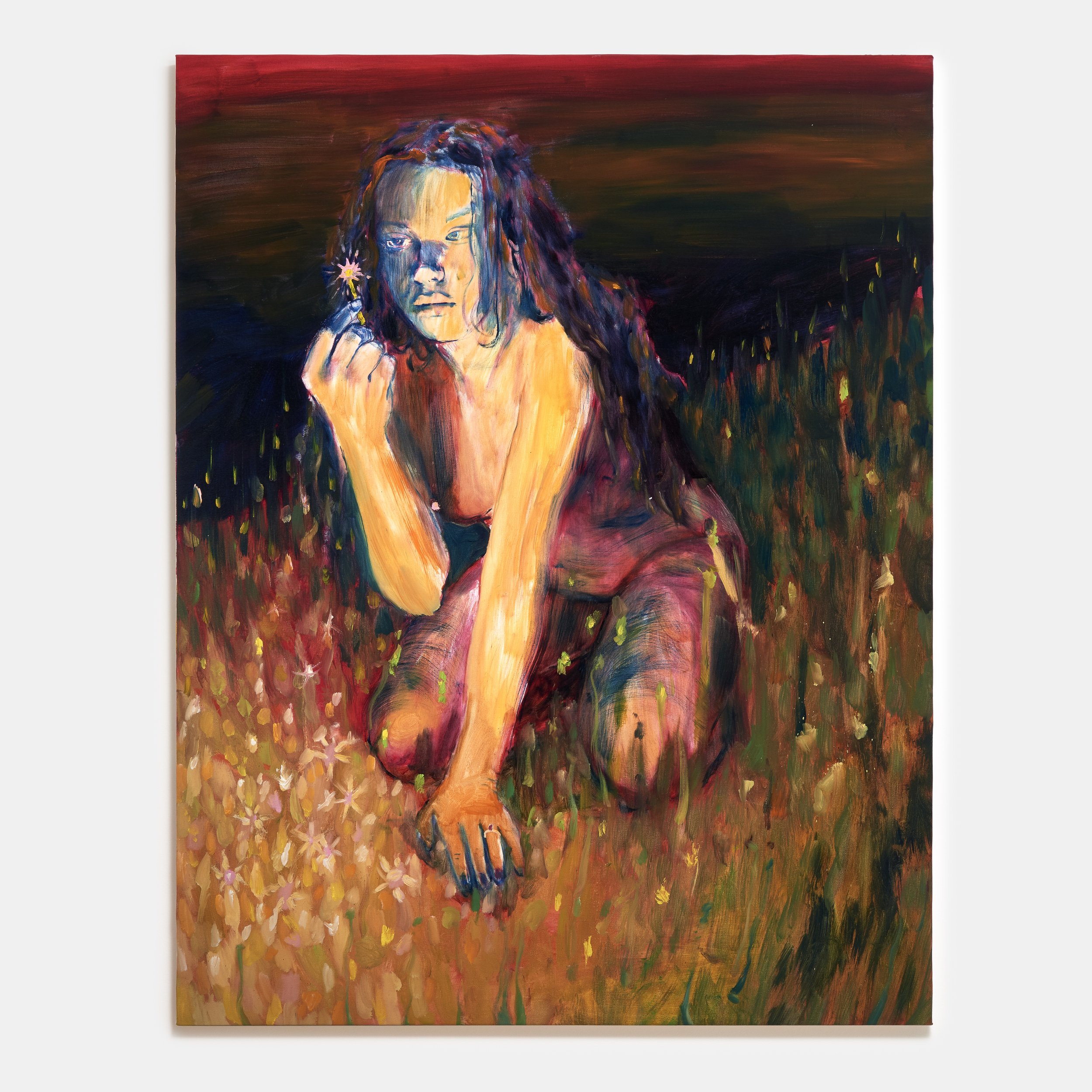

Caroline E. Absher, Magic Flowers (2021). Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

The larger first-floor room marks a change from the ground floor in its addition of furniture and ornamentation to complement the surrounding artworks. Much of the room’s artworks contain an element of magical realism to them, with figures who could have been plucked straight out of a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel. In one corner of the room, Loren Erdrich’s Your Face is Bangin’ (2018) is reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s Scream, yet the artist presents a female figure in the middle of a fleeting moment of pain and pleasure in which she lets go of her inhibitions to enter this altered state. Situated beneath this artwork is a classical-style bust of a woman, highlighting the progression of representations of the female form throughout time. Promoting the innocence of the female form, Caroline E. Absher paints Magic Flowers (2021) as a representation of a moment from her childhood. The artificial light coming from the bottom-left corner of the composition focuses on the figure’s upper body and face, as she looks with wonder at a flower she has just picked from the field around her. The combination of bold brushstrokes and complementary colours produce a painting full of wonder and beauty, in which the viewer is transported into this world of childhood innocence that has been long forgotten. While Lily Kemp’s Dreaming in Gold (2021) depicts a moment of innocence as two women relax in a natural landscape, the artist explores the exoticisation of women of colour in the media and the canon of art history. What immediately drew me to this work was its print-like quality due to the flat colours employed by the artist and the crispness of each element’s edges, however, each section of the work has been hand-painted which is an incredibly impressive feat.

Exhibition Installation Shot. Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

Kemp’s style is juxtaposed by the traditional academy-style portrait by Sarah Longe titled Just Having a Think (2021). Taking inspiration from classical imagery, such as The Fall of Man, Longe revisits these subjects with black figures as a commentary on the pervasive whiteness of art history. The central figure stares directly at the viewer and I noticed no matter where I was in the room, her eyes still followed my gaze. As a result, the figure seems to cause the viewer to constantly be reminded of this restricted canon. Lastly, I want to mention Alexi Marshall’s linocut print Bloodsport (2021) as its medium and technique stand apart from the other artworks in the room. Its psychedelic colour scheme matched with the modern-looking female figure manages to make a technique popular for printmaking in the early-to-mid twentieth century resonate with today’s audiences. The female figure is reminiscent of the Greek goddess Artemis, the virgin huntress, as she has shot a man through the heart with her bow and arrow. By aligning this figure with the Greek goddess, the artist employs this image as a metaphor for shooting down the male gaze.

Cecile Davidovici, Portraits of a constant dream VII (2021). Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

Peppered throughout the corridors are more of the exhibition’s artworks, again, reaffirming the domestic context and drawing the visitor further into the labyrinth of art. While they are all fantastic, my favourite by far is Portraits of a constant dream VII (2021) by French artist Cecile Davidovici. While much smaller in size compared to the exhibition’s other works, its medium separates it as unique from the others. Having been entirely embroidered, this magnificent work built upon layers and layers of thread presents us with one close-up figure that becomes two figures. The ambiguity of both figures is highly intriguing, and while they seem almost identical facially, they are separate individuals who function to act as representations of the inner self. One’s vulnerability is presented in the composition, with the layers of thread acting as brushstrokes on the linen.

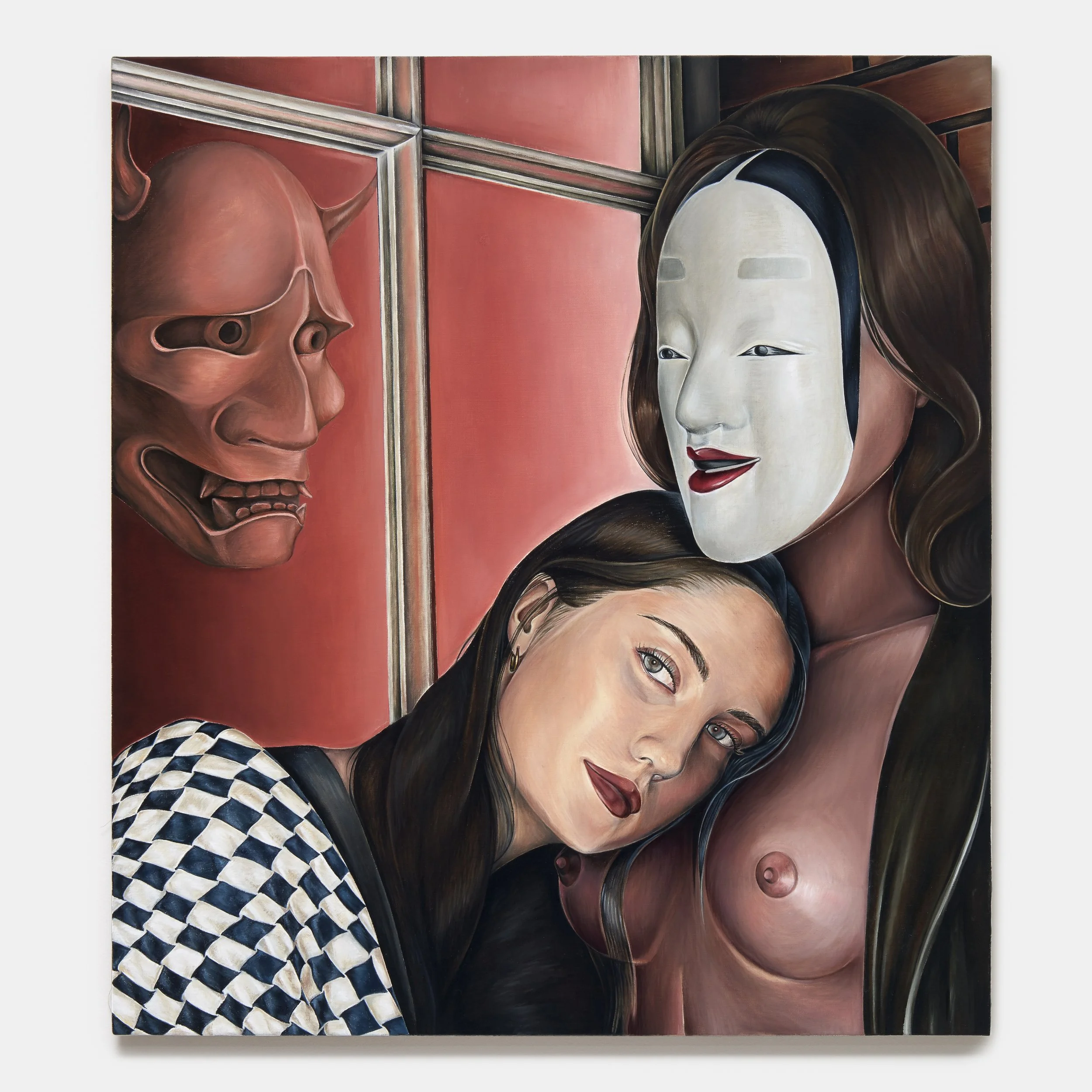

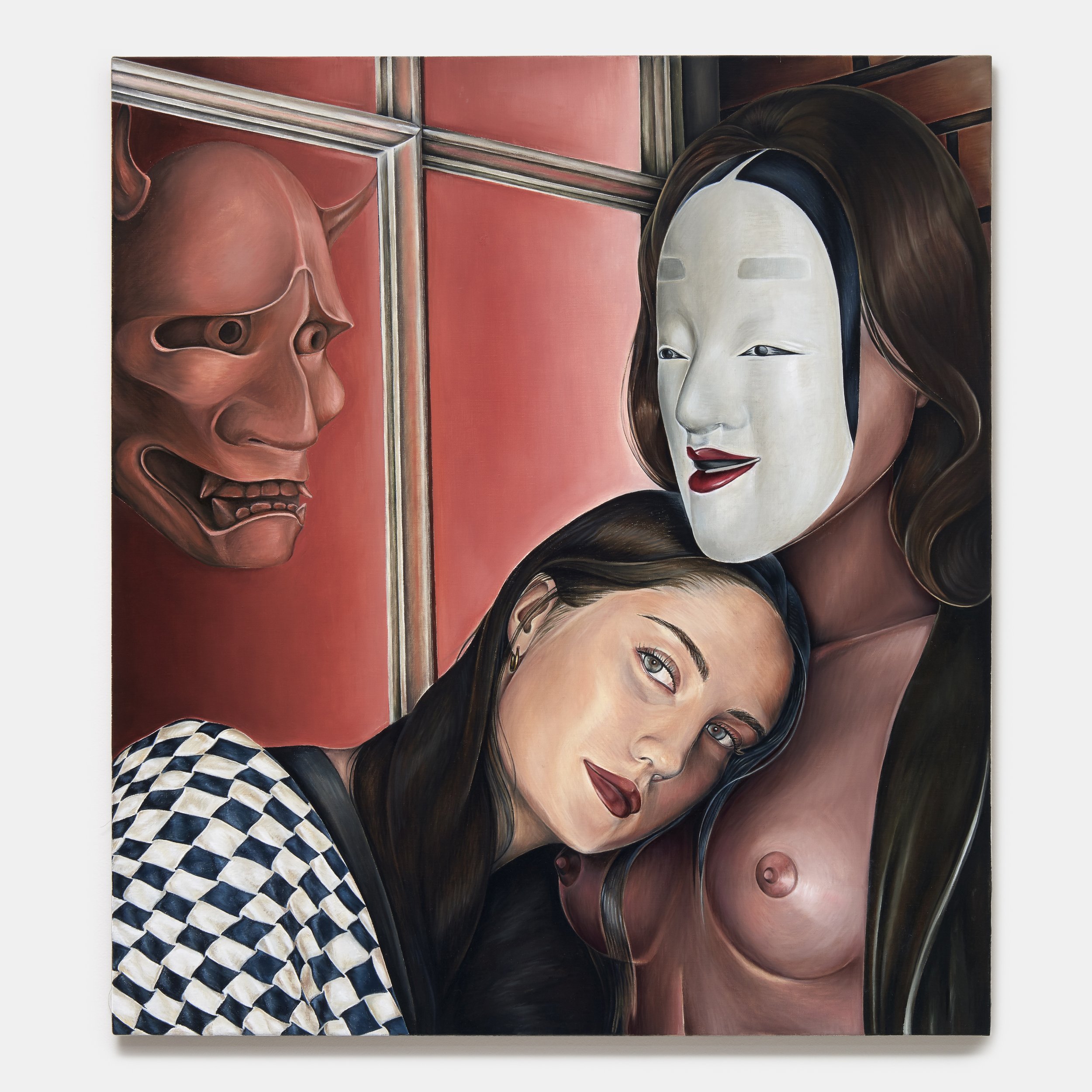

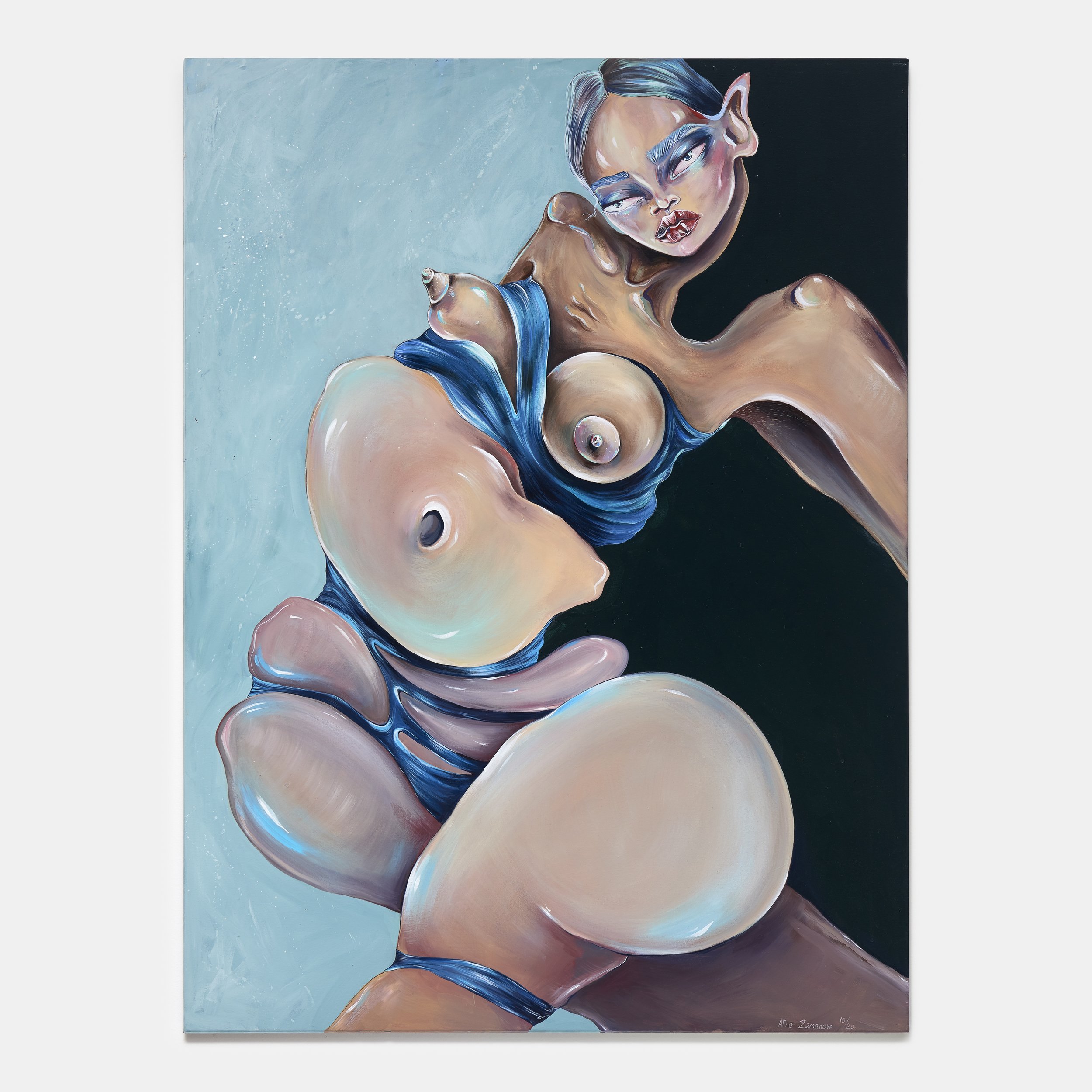

The final room at the top of the gallery space offers a change of mood from the other two rooms, presenting much darker themes and colour palettes to portray dualities of the self and resist pressures from society. Alina Zamanova implements body distortion in much of her practice, which is shown once again in her work Dark Side (2020). The female figure within Zamanova’s composition is heavily distorted, with a pixie-like face and tape wrapped around various parts of her body, to emphasise the female form. Much of the artist’s work focuses upon ideas of stereotypes of the ideal female body, which has been heavily influenced by the rise of social media stars who attempt to enhance their figures through plastic surgery and cosmetic fillers, all whilst promoting “loving yourself no matter what you look like”. On the opposite wall lies Ariane Hughes’s work Unfriendly Reflection (2020). The title promotes the exhibition’s theme of identity and creationism in that the viewer and the figure are forced to reevaluate their sense of self. The central woman lays her head on the chest of a masked female figure with exposed breasts, which begs the question of whether or not the relationship is sexual. As a lover of Japanese art and culture, I was intrigued by the use of masks from the Japanese Noh Theatre as they are laden with meaning. The white mask is a Koomte mask, representing innocence and purity. By contrast, the mask in the window is a Hannya mask, a representation of demonic power and suffering in Japanese culture. As such, the painting can be read as a struggle between the innocence of the self and the suffering of womankind.

Ariane Hughes, Unfriendly Reflection (2020). Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

Alina Zamanova, Dark Side (2020). Courtesy of Daniel Raphael Gallery.

As for my final thoughts on the exhibition, I just wanted to note that while I have not been able to discuss all the works on display, I can genuinely say they all meaningfully contributed to the exhibition’s themes as a whole. The gallery space invites the visitor in through its intimate feel that is unique to Daniel Raphael, as having been converted from a house. Each room is unified in its subversion of traditional presentations of the female form, whether it be through elements of magical realism, interesting poses or reflections upon the self. As such, the exhibition sheds light on the pervasiveness of the male gaze in the 21st century, yet it gives me hope for this new generation of artists who can aid women in reclaiming their power.

Get a Load of This! is on display at Daniel Raphael Gallery until May 31 2021.

By appointment only.

Explore the exhibition on Artsy.

Find out more at Daniel Raphael Gallery.